Yimby, taxes, expertise, state capacity, elections, economy

I am remiss. It is my nature.

Long suffering readers know that I now mostly publish on my drafts blog. But I publish excerpts of those posts here!

It is August, however, and I’ve yet to publish excerpts of June posts. I’ll do that below. Click here to skip to those!

Some reminders:

- You can subscribe to my posts by e-mail, lots of different ways.

- I host weekly “office hours”, Friday afternoons from 3:30pm Eastern US time, 12:30pm Pacific which is 7:30pm UTC (until we “fall backwards” in autumn). Just come to this link any Friday afternoon to join.

- I hope to build a comments forum (and much more) soon, but soon has sure taken a while. In the meantime, please feel encouraged to drop comments here.

June was a busy month!

There were three housing posts.

Yimboree, inspired by the excellent Ned Resnikoff, is probably the most comprehensive statement of my views on housing abundance and the YIMBY movement. (I’ve written quite a bit about this stuff in the past, see Microcities, There’s no substitute for a substitute, Home is where the cartel is, Zoning laws and property rights.)

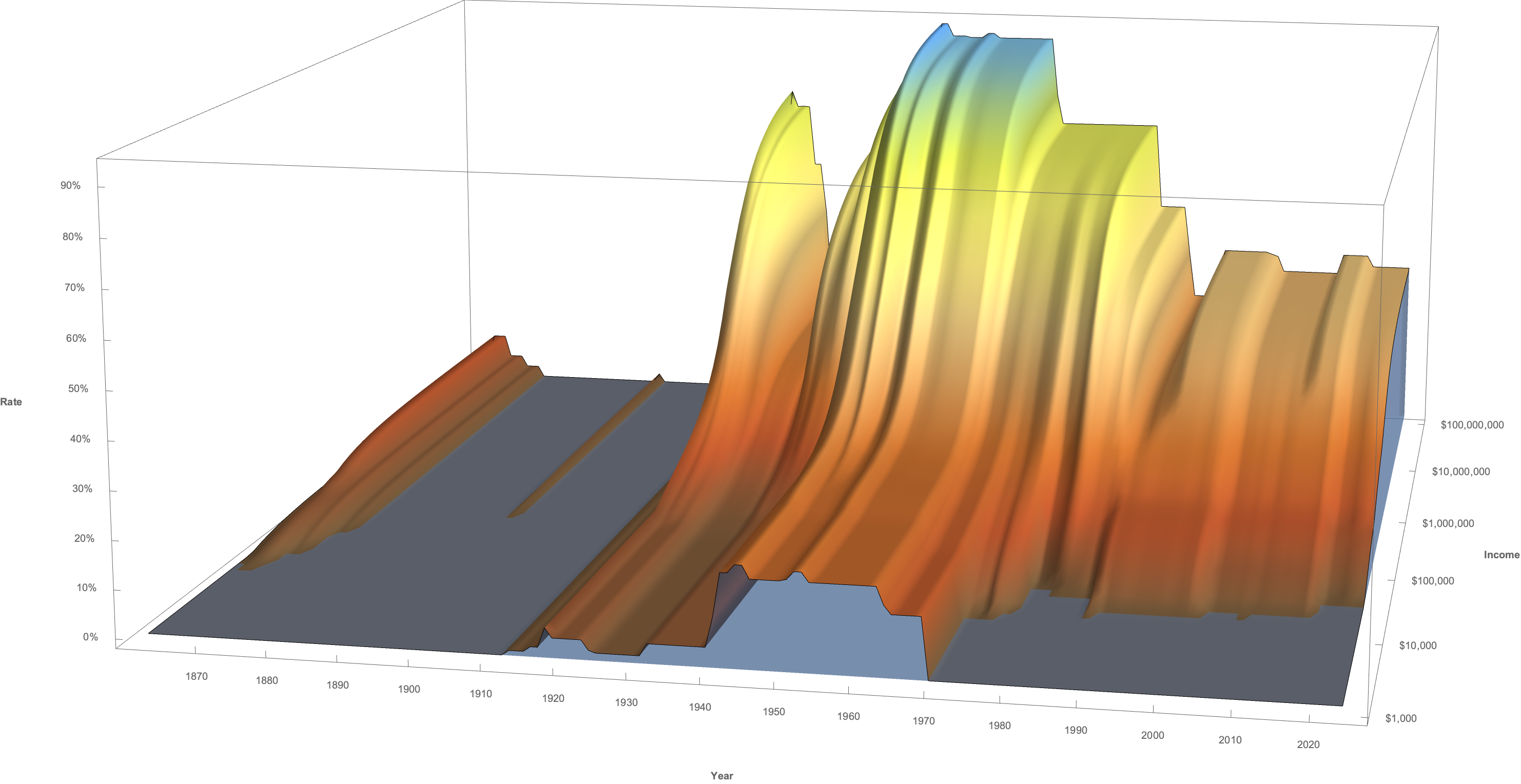

My friend Chris Peel did some amazing work computing a full history of effective US income tax schedules.

I made a pretty 3D picture of that in Mathematica, and then zoomed in on different eras to offer my own editorializing narrative.

Experts, can’t live with ’em, can’t live without ’em. The necessity of relying upon and sometimes deferring to experts stands in very real tension with values like democracy, accountability, and fairness. No, I don’t think deferring to an inexpert, unelected, corruptible and often unaccountable judiciary is any kind of answer to these dilemmas.

I think contemporary institutions and norms surrounding expertise and credentialing aggravate rather than mitigate the problem. Authority minimization is one attempt at an intervention. (I continue to think we should use community colleges much more extensively, rather than rely upon elite credentials, as a foundation for more democratically accessible and accountable expertise.)

People sometimes imagine that liberalism is associated with a weak, very “limited” state. I think that’s 180 degrees wrong. Liberalism can only thrive under a very strong and effective state. A state can afford to respect broad-brush, formal limits (which are desirable!) only when it is capable of stewarding a safe and prosperous social order despite those limits. I mean to write more about this, but State capacity and authoritarianism is a first attempt. (See also Tyler Cowen on “state-capacity libertarianism”, though I bristle at some of his specifics.)

Two June posts concerned the 2020 Presidential election, at least as it stood in the B.K. era. (Before Kamala).

Finally, also enmeshed in election talk, was a post on what a “good economy” even means. I think that’s important, but the lede was badly buried.

Let’s do the excerpts! In reverse chronological order, as always. These are June only. (July will follow soon.)

From Superdelegates (2024-06-29):

As old and stumbling as Joe Biden may have appeared on the debate stage, the Biden Administration has comported itself with tremendous intelligence. Should it entertain a change of leadership, let’s imagine that it will do so with the same intelligence. What would that look like?

From It isn’t sprawl if it’s dense. (2024-06-20):

Dense development is green development, almost wherever it is. It’s the density that matters, not the where.

There are roughly 340 million people in the United States. All of them need to be housed. The “footprint” of that housing, in terms of simple land area, land that can be neither wilderness nor farmland, is solely a function of average density. At suburban densities — call it 2000 humans per square mile — we require 170,000 square miles for our habitat. At Paris density, the same 340M people could be accommodated on less than 7000 square miles.

Density is overwhelmingly the factor that divides green from less-green development.

…

Human beings are clever, and people have gotten very good, especially in Europe and Asia, at planning and building dense, extremely desirable places to live.

That’s the prize.

We can do it too! And we don’t have to confine the work to the geographies where it is hardest to do, to places already inhabited at moderate densities whose residents understandably get grumpy when we come in with our bright eyes to reconfigure their worlds.

From State capacity and authoritarianism (2024-06-15):

States are the sine qua non of human capability. A certain kind of libertarian might resent this, but it’s obviously true. Human achievement and flourishing stratify across borders, favoring states that act and act well over states incapable of acting or that act poorly.

In a different era, when communication technology had not so completely tamed geography, the deficiencies of the US political system were kept in check by the diversity of an all-politics-is-local world.

Now all politics is national. Dysfunction latent in our arrangements has emerged, a blister burst, a festival of maggots dancing in the wound. We’re not going to uninvent the internet. Our national state will yield little but polarization, gridlock, and all-pay auctions in favor of political consultants, until we change the institutions that structure it.

We need state capacity now more than ever. We can do better than succumb to authoritarianism or gin up some war to find it.

But we will do one of those things if we don’t do anything else to restore a capable state.

Electoral reform is possible. It is easy. Nothing is more urgent, or more hopeful.

From Yimboree (2024-06-13):

I share a lot of values with YIMBYs!

I agree with YIMBYs that housing scarcity in desirable places to live is the signal domestic crisis of our time…

For a lot of reasons, I agree with YIMBY visions of urbanism…

…

I have never understood, at some deep basal level, why a reformer would choose to go for housing abundance in this way. It seems to me, historically, when metropolitan areas have grown in population quickly, the unit at which change has occurred is neighborhood or new town, rather than project-by-project infill in stably settled places.

My hypothesis is that we got this approach, and have kept doubling down on it, because a generation of young professionals really wanted to move to particular, already settled, places. They disliked that they either were priced out, or — to their credit! — they were not, but disliked that they were pricing out incumbent residents.

It is understandable that actual people coming of age want to move to particular existing places. It does an individual little good to imagine that someday there might be other wonderful choices. But once we shift our perspective from wanderer to reformer, an imagination of what could be, of alternatives we are capable of achieving that are just a bit less adjacent to the status quo, strikes me as essential.

From America is not already great (2024-06-10):

The question of whether an economy is good is as “objective” as your preference for strawberries and cream. What matters for the economy, overall and longer term, is as well captured in the moment’s economic statistics as GE’s quality of management was captured in its August 2000 stock price.

There’s no such thing as “objectively good”. We don’t all share the same values. We have radically diverse views about what a better future would look like. I want a prosperous future for us and so does Peter Thiel, but the shape of the worlds we aspire towards, what would count as prosperity, diverge. Some ways that the economy might “grow” bring the world towards Thiel’s vision, others towards my own. Any delta between the GDP numbers of those growings is not the thing that matters.

Expansion is most of the business cycle. We spent the majority of the last forty years in a “growing economy”. Most economists, most of the time, would have characterized it as a “good economy”.

What did all that good economy, in a cyclical sense, compose to as a secular matter? A world that is Pottersville, not Bedford Falls. A world in which the “successes” who buy our media companies and endow our universities are con men and financial predators, rather than people who produce more and better and cheaper goods and services. A world in which it’s hard not to juxtapose a booming stock market — yay! — with relentlessly expanding profit margins, companies “too big to care” (as Lina Khan memorably put it), private equity rolling up medical imaging and shutting down Red Lobster while blaming shrimp generosity rather than sale-leaseback financial engineering.

The American economy is dystopian, secularly. I agree that the Biden post-COVID cycle has not been so bad, has been pretty good along a variety of dimensions, although not as good as boosters protest too hard to claim.

It’s a point of light in a bowl of shit.

From Authority minimization (2024-06-09):

Democracy places an ethical demand upon experts that they on the whole are failing to meet. That demand is radical humility. It is human — and career-advancing — to play up ones abilities and accomplishments. Many of us quietly believe that if we had more say in how things are run, things would be run much better. Humility just at the moment when you might make a difference is a hard ask. But key to an expert’s job is to actively minimize the scope of their claim to authority. When communicating with the public or with political figures, they must strive to impose the narrowest set of constraints their expertise will allow, because their duty is to support, not to gainsay or foreclose, the democratic public’s discretion.

Legitimate authority derives not from expertise alone, but from expertise in service of the democratic public. If you intend to wield your expertise as an activist, if you learned about climate science to change the world, great. Present yourself as an informed advocate, make your case to the democratic public, educate, convince, try to help them understand things as you do.

But if you demand deference, if you claim that by virtue of superior knowledge, failing to adopt your policy positions is failing to “follow the science”, then you are mixing the roles of expert and advocate. The name for people who do that is “hack”. The prevalence of hacks in this sense — on cable TV, in think tanks, on social media, even among well-meaning scholars — has replaced a lot of public trust in experts with earned hostility. How are you supposed to feel about people who are actively disenfrachising you?

Expertise can be a resource to a democracy. It can be the weapon of a faction. But it cannot be both at the same time.

From Only the state can house us (2024-06-07):

[T]he core problem we face is much bigger than land-use. It is geographic inequality. We have created a country in which too few patches of geography are associated with vastly better opportunities and amenities than all the other places. As with individual inequality, some of this is “natural”. Some people are taller than other people, and will have better chances in the NBA. Some places are lovelier and more temperate than other places. However, the actual inequality we are struggling with is not due primarily to these differences, but to our social arrangements. There are plenty of lovely places in the United States that could host remarkable and desirable cities. That they don’t is a social outcome, not the result of any natural law.

So long as just a few places offer so much more amenity, liveliness, and economic opportunity than everywhere else, supply growth in those already built-out places will nowhere near match the tsunami of demand they face from people who would migrate there if they could. The deep flaw in YIMBY-ism is that problem they accurately highlight is orders of magnitude larger than what the solutions they identify, promote, and support can plausibly address. Yet the medicine they propose is divisive and painful to people in established, lived communities, and tend to serve the better-off in favor of the worse-off, as market-based solutions usually do. Regulatory caveats intended to counter gentrification, exhortations to upzone places that are affluent and coveted rather than communities poorer and already precarious are well and good. But they cannot overcome the basic physics of market action, to each according to his purchasing power, from each according to his desperation.

…

What YIMBYs get wrong is the actual nature of the scarcity they need to overcome. You cannot, will not, overcome the scarcity of San Francisco. What you can overcome is the scarcity of San Franciscoes. If you create more demand drivers, more places where it becomes desirable to live, where important agglomeration effects take hold, you reset the picture. All of a sudden, there are greenfields very near your demand driver, which you can develop at efficient density without colonizing established neighborhoods. Eventually, established neighborhoods in older desirable places will redevelop themselves, in ways their own selfish residents determine, as desirable alternatives elsewhere become competitive threats.

…

So far, the housing apocalypse has been a boiling-frog game of musical chairs. The housing situation has worsened in increments, and the losers each round have been the least well-off. That is precisely the sort of problem the American political system is built to ignore. We blame the losers, and segregate ourselves from them. (Until, of course, we find it is our turn to lose.)

But climate shocks are already beginning to change this. Well enfranchised, safely middle-class Americans are going to find themselves uprooted from homes they purchased as the foundation of their security, some directly by catastrophe, most by burgeoning insurance costs. We are already in a phase of socialized denial, which we have institutionalized into state-backed insurers of last resort. Very soon, we will see one of those insurers outmatched by nature. Bailouts will be arranged.

From that moment on, the fiscal calculus will have turned. State-led housing development will no longer be a matter of handouts to losers, supported out of self-regarding pity by liberals, subject to criticism and derision by conservatives. State-led development will be the only means we have of rehousing millions of hard-working families over a limited period of time.

From Even the losers (2024-06-04):

A thing I think people get wrong is this idea people love Trump because they think he’s a winner. They’d walk away if only he can be revealed for the loser he really is.

I think people like Trump because they know he’s a loser like they often are made to feel they are too. Donald Trump is obviously a loser. But he’s a loser who wins anyway, who is rich and famous and drives all the asshole winners fucking mad.

That’s why the weird apocalyptic “I am your retribution” talk works. He is the dick you don’t really want to be, but that you would be if you set your resentments and anger free. His fight is, in that sense, your fight. Most of us are losers in a winner-take-all society.

…

We had the revenge of the nerds and they turned the world into a plutocratic surveillance nightmare. We are ruled by people who still think of themselves as the bullied smart kids and resent critics, despite the tsunamis of predatory cash they ride.

Now we may have revenge of the losers. I’m sure that will work out well.

From The US Federal income tax in pictures (2024-06-03):

Since World War II, US Federal income tax rates have fallen at every level. At middle incomes, they’ve deflated only modestly. But under the Kennedy and Reagan administrations, rates on ultra-high-income earners were demolished, in acts of social vandalism that have yet to be undone.

By throwing just a few small chicken bones to higher-income professionals and the middle class, mad occultists opened a portal to resurgent plutocracy. You can feel its dark wings thumping. We are living with the consequences.

Perhaps it’s time we reseal the portal.

My problem with California Forever was mobility, not having a mass transit connection to other communities invites more driving. The promise of buses is not enough, especially since the buses would be stuck in the same traffic with cars.

August 7th, 2024 at 1:41 pm PDT

link