David Andolfatto points out that US five-year real interest rates are now negative. Nick Rowe discusses the possibility that the so-called “natural” real interest rate could be negative, referring us to Frances Woolley’s discussion of the drag demographics might exert on real returns. (I’ll respond to Rowe and Woolley specifically in a little appendix to this post, but I want to start more generally.)

When we observe negative real rates, they are often attributed to something abnormal. Perhaps it is “depression economics” which has driven interest rates underground, or, as Andolfatto rather charitably considers, a misguided tax and regulatory regime.

I think this aberrationist view is quite wrong. I don’t think you can make sense of the last decade without understanding that the so-called real interest rate has been trying to fall through zero for years. Only tireless innovation by the men and women of Wall Street prevented negative rates long before the traumas of 2008. A deep cause of the financial crisis was a simple expectation: That lenders ought to earn a “decent” real, risk-free yield even while a variety of trends — skyrocketing incomes for the 0.1%, the professionalization of investing, leverage-induced risk aversion, China — were creating Ben Bernanke’s famous savings glut. The market response to a global savings glut ought to have been sharply negative real interest rates for low risk savers. But as a society, we resent and resist that capitalist outcome. It is well and good for markets to drive the price of undifferentiated labor asymptotically towards zero. But God forbid that “savers” not be paid for supplying a factor that turns out not to be scarce. Instead, an alphabet soup of financial innovations was conjured to transform bad lending into demand for low risk money, and thereby support its price. Now those innovations have failed, and the fact of negative real interest rates is plainly before us. But we are still, desperately, resisting it.

There is no such thing as a “natural” anything in economics. Economic behavior is human artifact and artifice. When economists call anything “natural” — the natural rate of interest, or of unemployment — you should recall Joan Robinson’s famous quip:

The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of ready-made answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.

The word natural is always used to hide the constructed context in which an outcome occurs, to disguise human institutions as immutable facts and thereby exclude them from controversy. What was the “natural” real rate of interest in 2006? According to TIPS yields, 5-year real interest rates were about 2.5%. But those rates were observed under the institutional context of a structured finance boom which transformed a lot of loose credit into allegedly risk-free lending demand. Was that rate “artificial” then? Today those same rates are -1%. Is this “natural”?

Ultimately, the words are meaningless. The level of interest rates that prevails in the market will be the result of a mix of institutional choices and economic circumstances. For now, we are in a bit of a pickle, because if we are “conservative” — if we stick with familiar institutional arrangements — we end up with outcomes that are violently disagreeable to our cultural prejudices. In social terms, a negative real rate of interest means that prudence is a cost, not a virtue. Caution is a greater vice than spending what you have and hoping for the best. Savers must be punished for their thrift.

In a sense, this is perfectly “natural”. Current spenders assume risks of future deprivation that current savers are unwilling to accept. Why shouldn’t spenders be paid to bear that burden? Transforming present resources into future wealth is uncertain and difficult work. Savers’ expectation of a positive real interest rate amounts to a demand for time travel cheaper-than-free. Why should such unreason be accommodated? The sense of entitlement carried by savers in our society would put any welfare queen to shame.

So, are negative real rates the way to go? Should we just tell savers exactly what we tell laborers? The price of the factor you supply has fallen. This is capitalism, quit whining and deal with it!

Maybe. But maybe not. In theory, a sufficiently negative rate of interest could restore a full employment, noninflationary equilibrium. I think that’s the market monetarist solution.

But it might not work out so well. Debt is a particular and problematic institution. If savers must pay borrowers for the privilege of carrying forward wealth, it matters in the real world whom they pay and how well those people do their jobs. Borrowers can always default, even after they have contracted loans at negative interest rates. If we try to restrict lending to only very creditworthy borrowers, we’ll find that real interest rates have to fall sharply negative to induce spending by people who would otherwise be inclined to save. If we allow more liberal credit standards, we’ll observe higher notional interest rates, but only as prelude to widespread defaults. We’ve seen that movie and it isn’t entertaining.

Ideally, a special class of borrowers, entrepreneurs, would invest borrowed funds in projects precisely designed to meet savers’ future consumption requirements. But in a sufficiently unequal society, the marginal saver may have vastly more wealth than is necessary to endow her own future consumption (including proximate bequests). There may be lots of ways to turn today’s resources into “future wealth” in a general sense, but goods and services in excess of what today’s lenders will be able to consume or reinvest in future periods are worthless to the people who set the price of money. The marginal productivity of investment may remain high technologically even as its marginal productivity to existing lenders turns sharply negative. (More accurately, both the marginal present and future dollar may have no consumption value to a lender, but in a accounting terms the value of a present dollar is fixed, while the relative value of a future dollar is flexible as long as there is inflation or some other means of circumventing the nominal zero bound.) It is the marginal productivity of investment to existing lenders that sets a floor beneath market interest rates. If we posit satiable consumption and sufficient inequality, market interest rates can approach -100% even while technologically fruitful projects go unfunded, because the projects would be of benefit only to people with little to offer the marginal lender.

The horizons of the future are broad, and lenders can invest in speculative future consumption like traveling to outer space rather than throw away money on nonproductive, low risk projects. People who seem now to have little to offer potential lenders might come up with new goods and services that savers will desire in the future. But debt is not the right instrument to fund speculative outlays, most of which will not be repaid. It would be an answer to the problem of negative real interest rates, if today’s risk-averse lenders would finance an exuberance of uncertain ventures. The majority would fail, but rare successes might be more valuable to lenders than certain negative returns on risk-free loans. This would require big changes on the part of current lenders and the institutions through which their funds are channeled. Rather than regulate a risk-free interest rate or scalar cost of capital, we’d need to find ways to encourage exploration, idiosyncratic judgment calls, and equity finance. It is foolish to presume that negative real interest rates alone will inspire a golden age of speculative investing.

If we rely too heavily on negative real interest rates to spur the economic activity, my prediction is that we will see a lot of false dawns and social strife. Savers of modest means are harmed and outraged by low market interest rates and use the political system to try to raise them. Regardless of macro models or market outcomes, we have a cultural bias against negative real rates. We hold prudence dearer than profligacy. We don’t work to teach our children to spend their allowances. We work to teach them to save. More people are willing to spend incautiously than are able to husband savings carefully. If we were to cast away the norm that saving is praiseworthy and spending decadent, rather than getting contingent, market-price-regulated spending/savings behavior, we might end up with a culture incapable of saving. We want most people to face a positive real interest rate, not because that is the price that equilibrates a market, but because positive real interest rates reward behavior we wish to uphold as a virtuous.

Our current negative real interest rates are not an aberration, but a product of longstanding and continuing trends. However, since neither those trends nor the negative rates are conducive a decent and prosperous society, it is foolish to refer to them as “natural”. We need to alter the circumstances under which full-employment requires that lenders pay borrowers to spend. We need to reshape “nature” until the new natural rate is positive. We need to understand the circumstances that lead investors to accept negative real returns rather than finance new ventures. We have to think about issues like income and wealth inequality, the structure of labor markets, institutional investor incentives, financial risk-aversion and deleveraging. We need to transform existing institutions, or invent new ones.

Appendix: Persistently negative real interest rates might have many causes. Nick Rowe and Frances Woolley tell stories that are essentially technological: Suppose we can bake a lot of bread today, but no so much bread thirty years from now. But we’ll need bread thirty years from now, and bread cannot be stored. Then no matter what we do with our surplus of bread, no matter who consumes and who saves, we’ll end up with a shortfall of bread in the future. Whatever we try to save, we’ll not recover. Institutional innovation can’t help us out very much, other than to arrange an allocation future pain.

But technological incapacity is not the only possible cause of negative real interest rates, nor I think the relevant cause at the moment. Unequal distribution can drive interest rates negative as well.

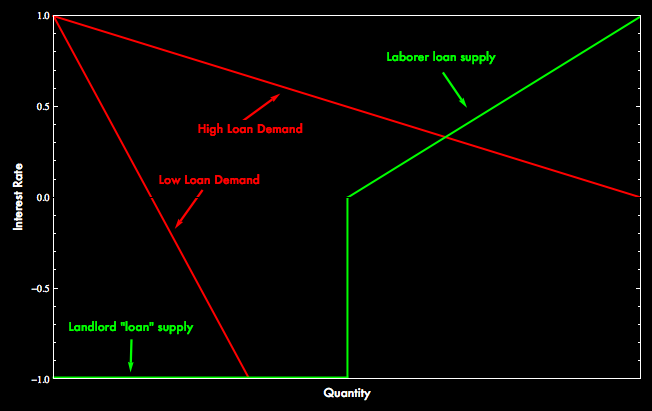

Suppose that land to grow wheat is scarce but labor to farm and bake it into bread is abundant. Land-owners and laborers are paid their marginal products, which at the limits of land scarcity and labor abundance means that land-owners receive approximately all the bread and laborers receive approximately none of it. Suppose that people prefer a bite of bread now to a bite of bread later, but that in each period, no individual can eat more than twice what their share of total output would be if total output were evenly divided. Land owners at full gluttony can eat no more than a small fraction of potential output, and they cannot store the surplus. Technology and population are stable, but land owners face negative real interest rate. There are laborers who would be glad to borrow the surplus bread, but they have no capacity to repay. The real interest rate on the bread lending market would be -100%.

In this economy, if a government were to tax land owners in every period and redistribute total production by lottery, so that each individual receives a per capita share of production in expectation, but variable amounts in practice, a wheat lending market would arise in which people receiving lower-than-average shares borrow from lend to people receiving greater than average shares at a positive real interest rate determined by agents’ time preference. Technology and population remain perfectly stable, but positive real interest rates arise as a function of institutional choices.

To be clear, I don’t think that the bread economy I’ve described is a remotely useful model of our actual economy, or that stochastically equal redistribution is remotely desirable public policy. But in response to Rowe and Woolley, while it is certainly true that technological limits can force real interest rates negative, it does not follow that observed negative real interest rates reflect technological limits. Observed interest rates are a function of distributions and institutions as well as technology, and it is perfectly possible that institutional innovation could cure observed negative real rates, if in fact we want them to be cured.

Update History:

- 8-Nov-2011, 2:25 p.m. EST: Changed “loose lending” to “loose credit” to avoid repetition of the world “lending”.

- 11-Nov-2011, 1:35 a.m. EST: With respect to who borrows from whom. See scratch-and-update in second to last paragraph. Many thanks to commenter ferd for pointing out the error.