How to fix the Euro

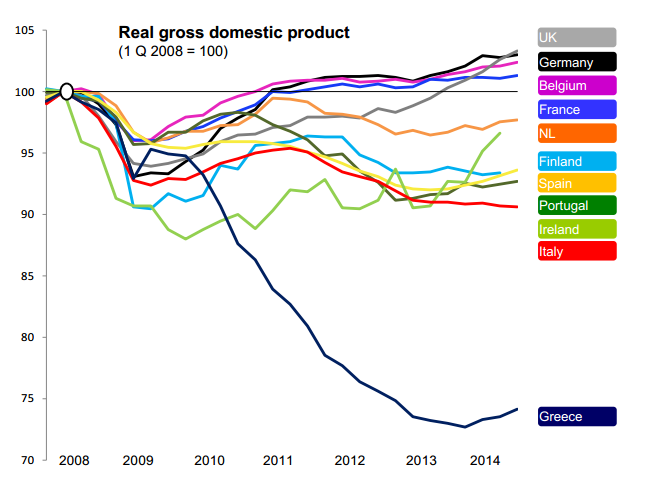

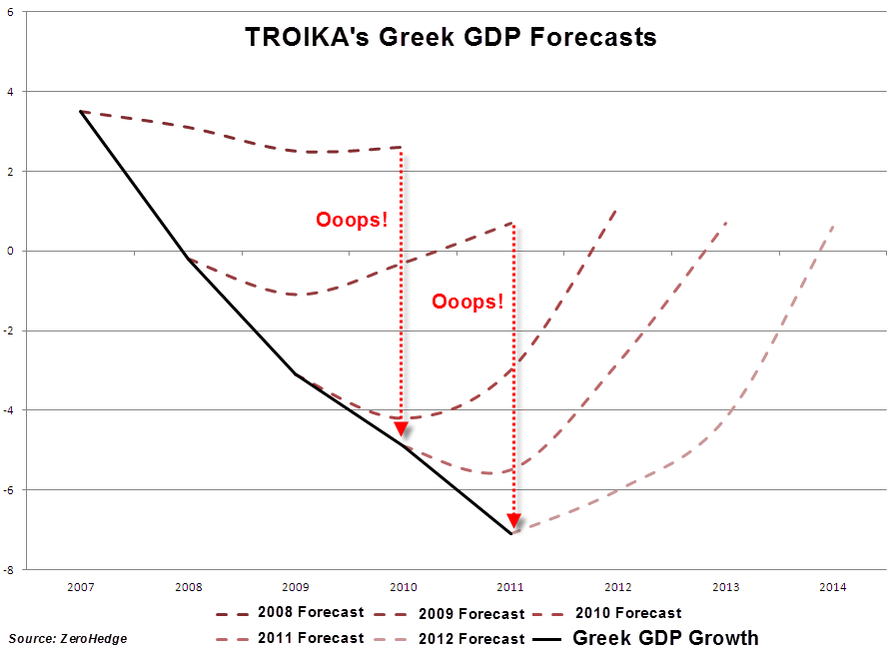

I broadly agree with the Angloamerican consensus about the, um, challenges associated with the Euro from an economic perspective. (David Beckworth has a very nice explainer.) We do understand that the Euro was adopted for political more than economic reasons. Unfortunately, with the benefit of hindsight, the hoped-for political benefits of the common currency seem to have materialized less than the long-warned economic problems, and the economic problems have now poisoned the politics. But we are where we are. I think it unlikely that the Euro will be dismantled except in the context of a crisis that would put the whole European project at risk, even more than recent crises already have. So the challenge, I think, is to come up with institutions that would help mitigate the economic flaws of the common currency, and that might be acceptable in a political union whose electorates, for the moment, feel no great solidarity with one another. Ideally, Europe might pursue a US-style union, where transfers made upon universal criteria to households and business blunt regional wealth and income asymmetries, without provoking the indignation that direct intergovernmental transfers provoke (and would provoke in the US as well). But, after the trauma of recent events, I doubt that a Pan-European safety net will be politically achievable anytime soon.

If “ever closer union” is on pause for now, perhaps Ashoka Mody has it right when he advises, “To stay close, Europe’s nations may need to loosen the ties that bind them so tightly.” Mody’s specific suggestion is that Germany and other Northern European countries depart the Euro, replacing one very suboptimal currency area with two more reasonable blocs. He makes a good economic case, but the political symbolism of a Dollar/Peso Europe would be pretty terrible. I think there is a better way.

In the heat of the recent Greek crisis, many commentators (Coppola, Koning, Mason) noted that “membership” in a currency zone is not a discrete, all-or-nothing thing, but rather a continuum. Many people advised Greece to loosen its bonds to the currency zone just a bit by issuing its own scrip, not denominated in a new Drachma, but in the Euro itself. This is not a new or radical idea. Even in the United States’ famously functional currency union, the State of California has periodically resorted to issuing dollar-denominated “registered warrants” in order to sustain necessary spending through cash crunches. For related proposals, see Bossone & Cattaneo (1, 2), James Hamilton, Rob Parenteau, and of course Yanis Varoufakis.

Issuing Euro-denominated scrip would not mean leaving the currency zone, any more than California’s registered warrants took California out of the dollar zone. However, in the context of the current crisis, if Greece had issued such notes, it would have been interpreted as a first step away from full-fledged membership in the common currency. Looking forward, what would be better would be to normalize the practice, throughout the currency zone, of having governments make domestic expenditures (and only domestic expenditures) in scrip. Greece would issue scrip, and so would Germany. The characteristics of the scrip (but not the value) would be standardized across the Eurozone. In particular, each country’s scrip would be a zero-coupon security, to be redeemed in Euros at face value over an uncertain term. (I think fixed-payout, time-varying claims represent an underused design for securities; I’ve suggested them elsewhere.) Each week, each government would issue a new batch of scrip, to cover that week’s domestic payments. The rules for redemption would be simple: first-issued, first-redeemed, at a pace determined at the discretion of the Treasury without precommitment. Governments whose tax receipts easily cover their expenditures could choose to redeem the scrip nearly instantaneously (after some minimal period, perhaps one week). Governments that wish to run a deficit would redeem scrip more slowly.

The scrip would not become a de facto domestic currency. It would be too fragmented; each week’s vintage would have a different market value. Scrip would not be redeemable at face value to pay taxes.

What this all amounts to is a means by which states can finance themselves with forced borrowing from their own citizens who receive government payments. That sounds a bit mean, but it solves two important problems that currently plague the Eurozone:

International fragility — As the Greek crisis highlights, sovereigns ought not rely upon foreign borrowings in a currency the state cannot issue. The future is always uncertain, and when things go wrong debt securities must default or be renegotiated. That is awful even in small-scale private contexts. In an intersovereign context, it can lead to immiseration on a large scale through depression or war. Successful states mobilize the risk-bearing capacity of their own populations in order to finance government activity. Domestic politics can adjucate conflicts between local creditors and the public’s interest in government services in ways that outside institutions cannot. The interests of domestic creditors overlap much more with other domestic constituencies than the interests of foreign creditors do. International creditors have very little reason to support the work of a foreign government (other than taxation and debt service), while domestic creditors balance their interest in getting paid against other interests related to government performance.

-

No constituency for taxation — The Euro was conceived as currency of “prudence”, with its Stability and Growth Pact intended as a straitjacket on government borrowing. So it is ironic that the architecture of the Eurosystem destroyed the incentives of domestic constituencies to support efficient tax collection. By design, the Eurosystem preserved the practical ability of Eurosovereigns to borrow from the banking system inexpensively and at will (a privilege which remains intact, supported by the ECB, for all countries except Greece). Beneficiaries of government expenditures had little reason to support taxation, since the funds they wanted spent could be borrowed. More importantly, the Eurosystem absolved domestic constituencies of the usual consequence of undertaxation, that their incomes and saving would lose value from inflation. Ordinarily, creditors in any country are powerful constituencies for balanced budgets and “sound money”, which sometimes means cutting expenditures but also means raising taxes when expenditures cannot be cut. [1] While Eurozone states that borrowed (whether as sovereigns or through banking systems) did experience higher inflation than creditor countries, the difference was modest. Citizens knew that the value of their money was externally anchored, a Euro would always be a Euro. This imported stability hindered the emergence of any domestic constituency in favor of developing (and exercising) the state’s capacity to collect taxes.

If government domestic expenditures, including transfer payments like pensions, are made in the scrip proposed, the market value of those securities would be directly related to the perceived willingness and ability of the state to tax in order to retire the IOUs at a reasonable pace. The villains’ in lazy creditor morality tales — beneficiaries of the welfare state, govenment employees, vendors of goods and services to the state — would become powerful constituencies for building and maintaining an efficient tax system. This would restore the natural tension in domestic politics, a balance that Eurozone institutions uninintentionally destroyed, between domestic constituencies with an interest in taxation, and other domestic interests who would be net payers of tax and so lobby to streamline expenditures.

This proposal would not fragment the Eurozone. The Euro would remain the universal unit of account and medium of settlement. [2] The proposal would loosen the strictures on government expenditure compared to existing arrangements, but importantly, the risk associated with that extra fiscal freedom would be borne entirely by domestic constituencies, not by external creditors. It would restore to Eurozone states some of the tools they lost for managing domestic shocks, without requiring unpopular transfers or destructive borrowing from other states. It would strengthen Eurozone states, as polities.

The lesson of the Asian Financial Crisis and the extraordinary reversal of financial flows that many Asian countries were able to engineer is that the strength of a state is largely a matter of its capacity to mobilize domestic risk-bearing, rather than rely upon external finance. Eurozone institutions unintentionally short-circuited that capacity. It’s time to restore it.

Some institutional details:

Universality — This proposal should be implemented universally within the Eurozone, as an institutional innovation for the common currency. Within states that have no immediate need for new borrowing, the market value of “state expenditure notes” would be par, and no one would have reason to complain. However, if adoption of the notes were made optional and became associated with perceived-as-weak states, states that could really benefit from financial flexibility and incentives to develop an effective tax system would be reluctant to adopt them for fear of stigma. A fig leaf — “Even the Germans do it!” — is the one concession to solidarity that this proposal requires. Otherwise, this proposal segregates risk, rather than blurring borders, which might be a relief to Northern European publics.

Liquid Markets — All states would be required to arrange low-transaction-cost, liquid markets in state expenditure notes. Recipients of government expenditures who need to make immediate payments may choose to convert them to cash Euros at a discount. Others may hold their notes and await redemption at face value. The discount to face at which the securities trade would provide ongoing information about the perceived fiscal strength of the state, and a very visceral incentive for recipients to see to that strength.

Banking considerations — Domestic, and only domestic banks, would maintain custody of the notes on behalf of customers. However, the notes would be held in segregated accounts, not on bank balance sheets. The Eurozone desperately needs to eliminate bank exposure to the sovereign debt of member states. These proposed notes would be an unusually speculative form of sovereign debt, and absolutely inappropriate as bank assets. Banks would merely provide the service of holding notes for customers and liquidating them into customer accounts on demand, as an important convenience and at regulated spreads.

Definition of “domestic expenditures” — A “domestic expenditure” by a member state would be defined as a payment to a domestic bank account. All domestic bank accounts would be paired with custodial accounts for expenditure notes. States could insist that transfer payments be made to domestic accounts, and might prefer to purchase goods and services from firms with domestic accounts as well. Foreign firms wishing to do business with cash-strapped governments and willing to accept the financing terms might open local bank accounts, but in general this restriction would ensure that most of the notes are spent to domestic constituencies. Speculation in the notes by nonresidents would be discouraged, in order to keep incentives (maximize the rate at which notes can be redeemed) and control (vote and participate in domestic politics) well-matched.

Interaction with traditional debt — The rate of redemption of expenditure notes would be entirely at the discretion of the issuing government, while coupon and principal payments on traditional debt must be made on a preagreed schedule. In that sense, one might imagine expenditure notes to be “junior” to Treasury bills and bonds. However, in the event of default, debt restructuring, or sovereign refinancing by ESM / EFSF / ECB / IMF / etc., expenditure notes would be treated as senior to other Treasury securities. (Expenditure notes would be treated analogously to uninsured deposits in bank capital structures, available for “bail-in” only after other unsecured creditors have been wiped out.) This is very important, as it would encourage buyers of traditional securities to price the credit risk of the sovereign’s full capital structure, including the debt embedded in outstanding expenditure notes. Formal seniority also reduces the risk that foreign creditors will be able to use the notes to shift the consequences of their own poor credit allocation decisions onto involuntary domestic creditors.

Of course, short of an outright restructuring or refinancing, governments might choose to slow redemption of expenditure notes in order to retire traditional debt, which is fine. Strong domestic constituencies would limit the pace of such a reprofiling. If, eventually, finance via expenditure notes largely replaces traditional sovereign debt, that would be great. Domestic finance is much better for a polity than foreign finance, and variable maturity notes decay in value gracefully, while overextension of traditional debt causes disruptive oscillations between complacency and crisis.

Update: Perhaps the first proposal to address Eurozone problems via issuance of scrip came from Warren Mosler. When putting together cites for this post, I did not find that proposal where I had linked it previously, and simply omitted it. Fortunately, my commenters are not as lazy as I am, and point me to this 2012 version by Mosler and Philip Pilkington. I am very glad to acknowledge the prescience of Mosler’s work and the very strong influence of his “Modern Monetary Theory” on the thinking that underlies this post. My apologies for the original omission, and thanks to commenters JKH and Roberto for helping to remedy it.

[1] This may seem a little far-fetched in a US context, where creditors prioritize low taxes over any other thing, but that is unusual. The United States’ “reserve currency” status blunts the effect of debt and money issue on currency value, so creditors have less reason to prefer taxation to borrowing. In a small country with a floating currency, the potential hazard of overissuing government paper is more immediate to holders of local currency debt.

[2] Currencies are no longer “media of exchange” except for very small transactions. They are means of settlement. When I make a purchase with my credit card, I do not trade dollars for goods, but issue a bond (guaranteed by my bank) that may be eventually settled in government money if the recipient demands it. Currencies are media of settlement, not exchange.

Update History:

- 24-Jul-2015, 5:20 p.m. EEDT: Bold update highlighting and acknowledging MMT and Mosler’s earlier work.

- 24-Jul-2015, 10:30 p.m. EEDT: Added links to Bossone & Cattaneo proposals.