There’s no substitute for a substitute

Eric Fischer, after heroically reconstructing San Francisco housing data for much of the 20th Century, published an analysis of the determinants of median rents. The hat tip goes to Tyler Cowen, who concludes “basically SF is ****ed.” Less pithy commentators did what less pithy commentators usually do, and used the analysis to claim that it basically supports their preconceptions and what they have been saying all along. It was only March when Hamilton Nolan helpfully concluded, “Build some housing, assholes. A lot!”.

Well, far be it from me to buck the trend. The analysis supports my preconceptions and what I’ve been saying all along.

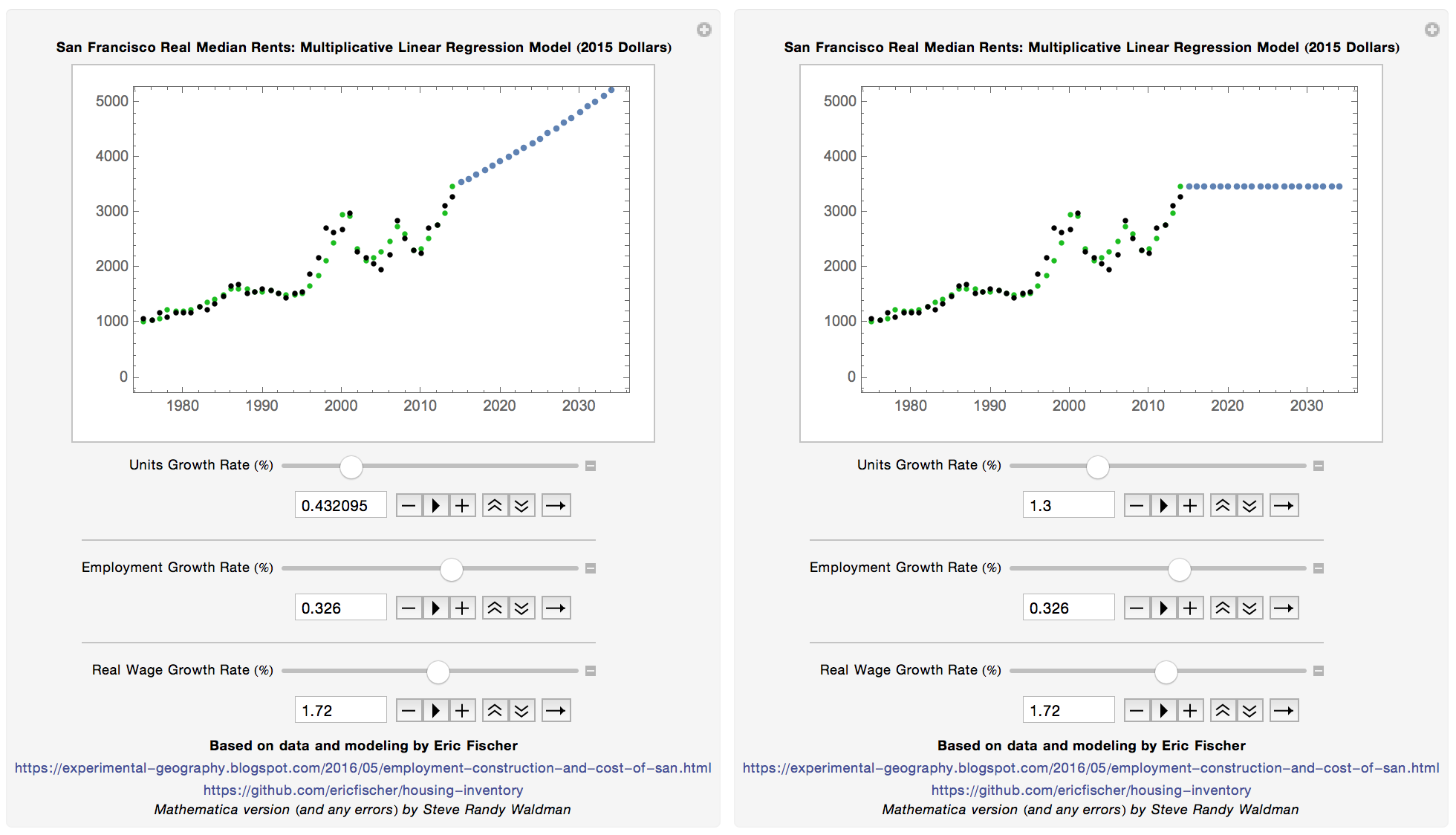

Basically, Fischer estimates a model that puts plausible magnitudes on the price effect of new housing supply. How much new housing would we actually have to build in San Francisco to address the housing affordability problem? The model is certainly contestable, but at least it gives us plausible magnitudes to talk about. To stabilize real rents at their current, absurdly unaffordable level, Fischer finds that the number of housing units would have to increase in real terms by 1.5% per year, holding other factors constant. [*] So, is it plausible that San Francisco could build its way out of its housing crisis? As Fischer notes, that would imply a unit growth rate more than 3 times the average rate since 1975. Hamilton Nolan of build-some-housing-assholes fame concludes that

Those fortunate enough to have nice places to live in San Francisco (and the rest of the Bay Area) have had decades to get this right. And they haven’t. Drastic measures are in order.

Decades! Hamilton, you are more right than you know. The last time San Francisco achieved a unit growth rate of 1.5% was in… 1941. So many decades of NIMBYs! What was really different about 1941 compared to now? No exclusionary zoning regs? No pesky environmentalists? Maybe! But perhaps a more parsimonious explanation is the one that Fischer himself gives.

From 1935 to 1943, the Central Sunset and Parkmerced filled in. From 1944 to 1954, the Outer Sunset and Ocean View were built. And that was essentially the end of the easily developed greenfield housing.

In the history of San Francisco, 1.5% unit growth has never been achieved via “infill” development of an already occupied peninsula. There was a brief boom that managed a few years of 1% to 1.3% growth in the mid-1960s, but during that period developers “still could fill in the hillsides of Twin Peaks and above O’Shaughnessy Boulevard.” After that, the vacant land was gone. From 1967 to the present, the city managed a growth rate of more than 0.5% in barely one third of years (17 years out of the 48 from 1967 through 2014, when the data ends.) During the post-greenfield, post-1967 period, which years were best? Was it during the good old days before “homevoters” shut down the “growth machine” with their exclusionary zoning laws? No. The best years of the post-1967 period in terms of unit growth were 2008-2009, and then again in 2014 (the most recent year in Fischer’s data). No year exceeded 1% unit growth. But 2009 and 2014 did achieve a remarkable 0.9%.

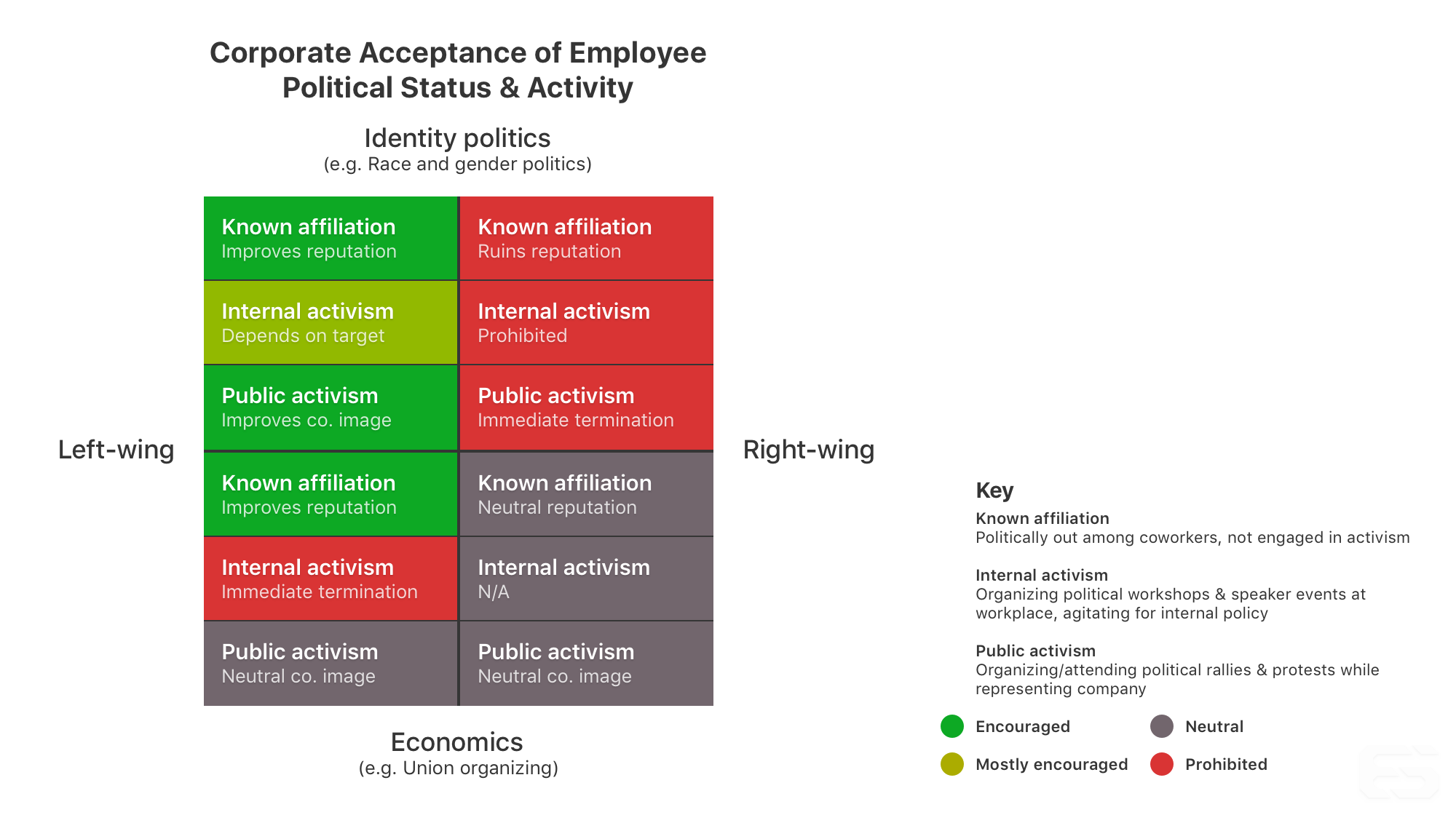

Conventional wisdom has coalesced on the notion that it is NIMBY-ism and exclusionary zoning that are responsible for the crazy, crazy housing prices in San Francisco and other high rent cities, and so the solution to the problem must be a bloody, painful battle to overcome greedy incumbents’ attachments to their homes and neighborhoods. But before we destabilize neighborhoods and displace humans in the name of housing supply, we might want to ask, will all that pain really address the problem? Sure, at the margin, more construction will yield lower prices. And I understand that, following construction boom years, rental prices have stabilized in cities like DC and Chicago.

But within developed cities, construction booms are short and finite. Chemotherapy may be worth the nausea and hairloss if it adds years to ones life, but would it be worth it for an extra week? Infill densification is socially painful and physically expensive in terms of demolition and retrofitting infrastructure. And, yes, buying off the evil NIMBY’s and the permitting authorities who serve them adds to those costs. But how many examples are there of cities that have grown their housing stock in place at anything like the rate that would be required to meet the burgeoning demand in San Francisco or New York? Before we wage war on ourselves, maybe we should inquire whether victory is plausibly achievable. And, if it isn’t, maybe we should come up with a different plan?

The situation is even worse than it appears. The current craze, the only hope on the political horizon, is “affordable density“, which would eliminate regulatory impediments to construction for developers who reserve a percentage of units for means-tested tenants who would pay below-market rent. This trend reflects some mix of a well-intentioned attempt to address displacement and pragmatic acknowledgment that a city that has priced out its teachers and service workers might have a hard time functioning. However, an awkward fact of market pricing is that effective supply is not the number of units built, but the number of units actually made available to the market. Compared to a laissez-faire counterfactual in which redevelopment simply pushes poorer residents out of the city (often the case historically), every human not displaced diminishes the degree to which densification reduces market-rate rents. A market is not a dinner party. The higher the affordable housing requirements, the greater the rate of unit growth required to stabilize market-rate prices. Have we mentioned already that infill unit growth is really hard?

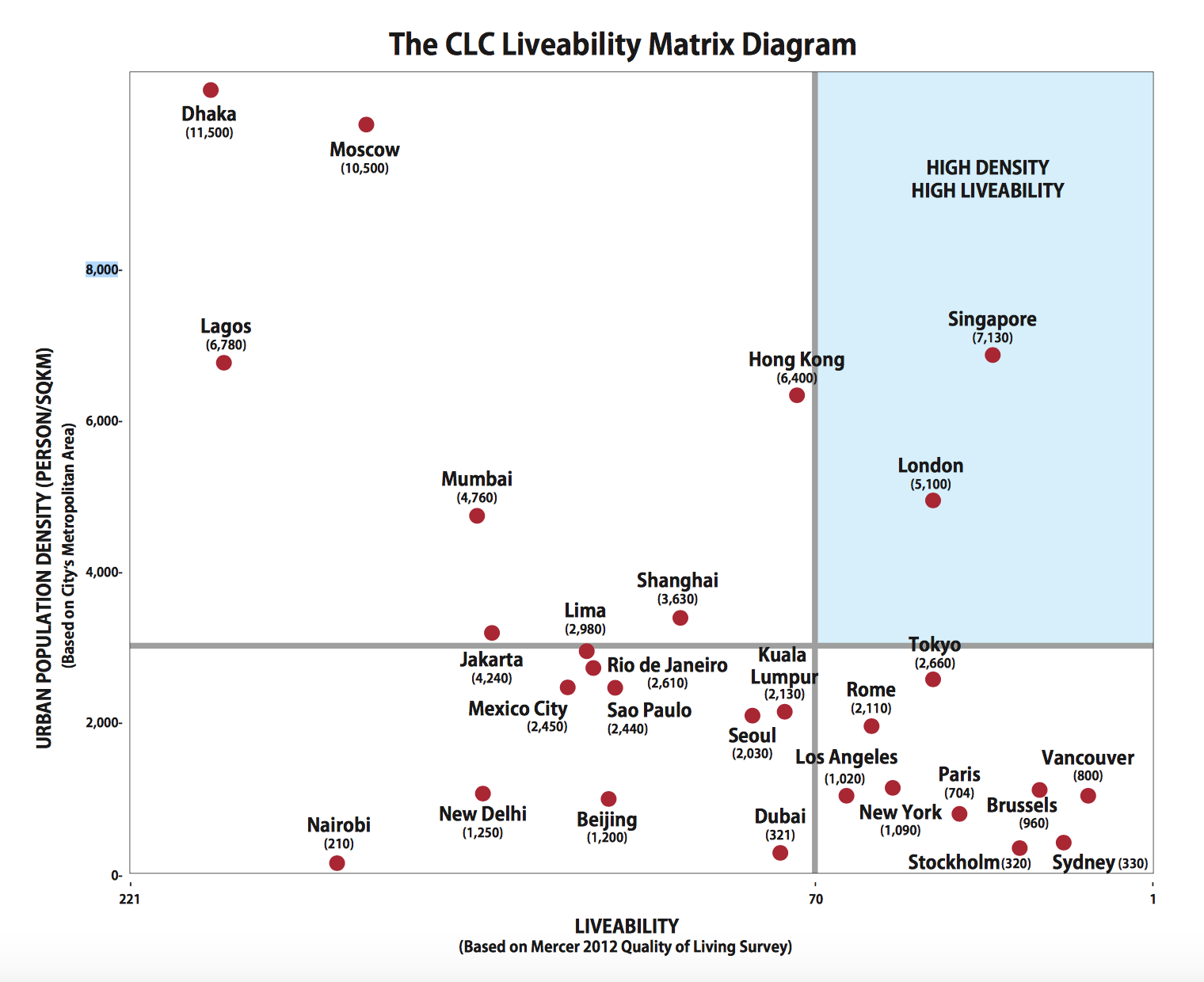

Cities evolve. They grow, they change, they do become more dense. And that is great. San Francisco NIMBYs are always on about Hong-Kong-ization or Manhattanization of the city. I like Manhattan and Hong Kong, and would be excited to see San Francisco’s aesthetically blah, largely single-family-detached west side turn fun like that.

But those neighborhoods are already inhabited. People live in the single family homes. They plant gardens in the generous backyards. In time, I hope those neighborhoods will change, and become more dense. I’m for a whole lot of redistribution, but there are reasons why civilized countries redistribute via financial tax-and-transfer rather than “land reform“, i.e. direct reallocation of real resources. To people who characterize homeowners’ informal sovereignty over their neighborhoods as a subsidy to the “upper middle class” at the expense of the “economically vulnerable”, I’d ask a few simple questions.

In a country where the homeownership rate is more than 63%, is it right to characterize homeowners broadly, even in San Francisco, as “upper-middle class”? Many homeowners have lived in their homes for years, and many new homeowners are mortgaged to the hilt.

Given that even an ahistorical, sustained trebling of unit growth would probably only stabilize, not reduce, the real price of housing in San Francisco, is it fair to characterize the people who would be helped by increased space for new residents as the “economically vulnerable”?

And given that, for perfectly understandable reasons, homeowners and residents resist fast-paced densification of their neighborhoods, which homeowners and residents would most likely be forced to tolerate changes they dislike or that threaten the value of properties? San Francisco has its share of stunningly beautiful neighborhoods affordable only to plutocrats. Will we put high-rises in those neighborhoods? Or, in the anodyne language of economists for every bad thing, will it be the economically vulnerable who must “adjust”?

Is Tyler Cowen right, then? “Basically SF is ****ed?” No. San Francisco could be just fine. The thing about San Francisco is that while greenfields have been exhausted in the city, the San Francisco Bay Area is largely undeveloped. We are always arguing over San Francisco, or Palo Alto (ick). Outside of the 47 square miles of San Francisco proper are almost 3200 square miles in San Mateo, Santa Clara, Alameda, and Contra Costa counties. (I’ll leave out the hoity-toity North Bay counties — Marin, Sonoma, Napa — but if it’s Latin-America-style land reform you want, the vines there are ripe for revolution!) Nobody wants new suburban sprawl, thank goodness. But dense development is not sprawl, even when it is greenfield development. When I argue that Singapore is an example we look should look to, people think I’m trying to make some left-wing point about public housing. I’m not. I don’t actually care very much about that. What excites me about Singapore is this:

It’s silly to characterize what Singapore does as “basically greenfield suburban growth“. Singapore’s new towns are denser than any US city, and nicer than most of them. They are designed for their density, not retrofit. What distinguishes Singapore is a “can do”, dirigiste approach to developing new living space, and a remarkable competence at making density green and livable. Singapore is an exuberant site of architectural experimentation, in both private and public building projects. Singapore’s “new towns” can house 100,000 people in less than 5 square miles. In the San Francisco Bay Area, there is plenty of space for Singapore-style new towns. Even Back East, room could be found for these compact conurbations.

Every piece of Earth has its stakeholders. As with densification of existing cities, plans to build new cities and their supporting infrastructure will provoke bitter controversy. But stakeholders for exurban land are fewer and more dispersed, and so less intensely affected, than city dwellers. The fights will be more winnable and the victories more meaningful in terms of the numbers of new dwellings that can be constructed. In the old city, we are condemned to bitter struggle over what ultimately may be too little to matter.

There are glimmers of hope for new towns, even in the US. See The Economist on “ersatz urbanism” in Florida. But it is in the San Francisco Bay Area, with its dreadful, painful housing situation, and its science fiction tycoons (several of whom individually could provide the necessary finance) where a full-scale, ecotechnological US microcity should really be attempted.

Soon.

Personal Epilogue: I live in San Francisco. I am a renter. I live in a neighborhood with no pretty Victorians, on a block with little anyone would want to preserve for character. My personal preference would be for a lot more density, in my own neighborhood and many others. My apartment building, like the vast majority of SF multi-family dwellings, is rent-stabilized. I support San-Francisco-style rent stabilization, under which initial rents are “market rate” but rent increases are regulated. I think it is a good policy regime. I don’t think the $300-ish per month I may be saving (after a three year tenure, figuring two 10% rent increases) much impacts my views, but “none of us can be perfectly objective arbiters of our own conflicts of interest“, so you be the judge. I detest San Francisco’s high housing (and other) prices, and feel that the cost makes the city culturally gross, a place full of insecure people (very much including me) tacitly or not so tacitly competing in crude financial terms for the right to live here. Conversations always turn to housing, in overt commiserations or covert attempts to feel out where the other person lives, whether they have space, how they can afford it. As I said, it is gross.

Nevertheless, I don’t support the broad-brush anti-NIMBY, anti-zoning, affordability-through-density movement, because I think it is counterproductive. I want more housing, more density, and more development, but I don’t imagine those can possibly address affordability even over the medium term. I think that attempts to supercharge in-place densification i) will not succeed at any remotely sufficient scale; and ii) will cause real harm, and not just or mostly to unsympathetic upper-middle-class baby boomers protecting price-appreciation windfalls. I am very fond, intellectually and personally, of people like Matt Yglesias and Ryan Avent who have made strong cases for upzoning and densification as the way to go. They deserve congratulations for how persuasive their arguments have been. At least within my socioeconomic milieu, their ideas have become enshrined as conventional wisdom. But in my opinion — which of course might be mistaken! — these ideas have supplanted consideration of more effective and less difficult solutions to the very real problems they mean to address.