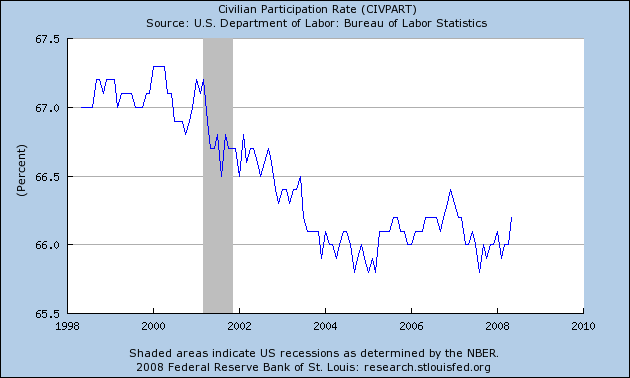

Much of the chatter surrounding the latest BLS release has focused on a spike in the denominator of the unemployment statistic, the fraction of the population either working or actively looking for work. Courtesy of the indispensible FRED...

About a year ago, David Altig (whose macroblogging I miss very much) wrote the following:

[Since 2000] you would be justified in claiming a broad-based decline in the number of people choosing to participate in U.S. labor markets. But I use the word "choosing" intentionally, as I'm convinced that the post-2000 changes in labor force participation rates (or employment-to-population ratios, if you like) reflect trends that are largely independent of the business cycle.

Much turns on the question of why people chose not to participate in the labor force this decade. A "business cycle" explanation, as I read Altig, would mean that people left the labor force because there weren't employment opportunities. They couldn't find a job, and became "discouraged workers", in the lingo. I agree with Altig that this is unlikely. However, unemployment statistics (very uneconomically) ignore price, and stagnant real wages over the period undoubtedly had something to do with the decline in participation. People chose not to work because they decided the money wasn't worth their time.

But it's also important to consider a credit cycle explanation for why people left the workforce. One has the luxury of choice when one can afford to do without employment. During a credit expansion, many people have that luxury, because one can live off of borrowing and asset appreciation. You can quit your shitty job and withdraw some home equity while you write the great American novel, focus on your music, or raise your children. You can go to school, even though you lack savings, because student loans are plentiful.

But when credit conditions tighten and asset prices fall, work becomes less optional. Quitting the rat race and pursuing your passion starts to recall the phrase "starving artist", and not in a charming way. Dad might decide he needs a job to make ends meet, even if that means putting the kids in day care.

Some argue that the US economy is structurally immune from the wrenching spikes in unemployment that used to accompany recessions, because employment has transitioned from volatile manufacturing to more mellow services. See, for example, this excellent analysis from Calculated Risk. CR chooses 8% unemployment as his threshold for a "severe" recession. But the US economy need not lose a single job more to bring unemployment to that level. If participation rose back to the levels of the late 90s without a commensurate increase in new jobs, we'd be there already we'd be at 6.6% unemployment right now. [Note: In my original calculations, I mistakenly entered 68%, rather than 67%, as the late 90s participation rate, significantly exaggerating the effect. My apologies for the error!]

When we ended welfare as we know it, back in the nineties, the slogan "Choose to work" might have captured the spirit of the times. It's ironic that more than a decade later, the apparent health of the American economy depends largely on how many people continue to choose not to work, now that the credit spigot has dried up.

- 10-June-2008, 12:30 p.m. EDT: Struck an corrected erroneous calculation of 8% unemployment if we returned to late nineties participation. Fixed a period that meant to be a comma.

| Steve Randy Waldman — Sunday June 8, 2008 at 12:49pm | permalink |

Here

And Here

This past weekend, 175,000 people sat for the CFA exam. Over 40% of them were from Asian countries. Many of those countries are subsidizing the exam takers. "Financial Analyst" will soon be a position outsourced to China for at significant cost savings, just as "Software Engineer" is with India.

In the second story, China is opening its first US-style law school, Peking University School of Transnational Law, and they've applied for accreditation from the ABA, so that their graduates can practice law in the US. They've also hired Jeffrey Lehman, Cornell Law School professor, and past president of Cornell and past dean of the University of Michigan Law School, to be the dean of the school. Likewise, students will be heavily subsidized.

In my opinion, the living standard of upper middle class college-educated folks in the US is about to take the same beating that working class and lower middle class folks have over the past few decades. In the technology industry, it already started a few years back.

You also mention the credit expansion allowing people to live on borrowed time and money, which is very true. Personal savings rates in the US generally hovered in the 7-9% range from the post-WWII period all the way through 1995, when they slowly declined until effectively hitting 0% around 2005 where they have since remained (and occasionally dipped into negative territory). With the free credit era ending last year, these people will have to either increase their incomes (unlikely) or drastically scale back their living standards.